“When you’re surrounded by people who share the same set of assumptions as you, you start to think it’s reality.” – Emily Levine

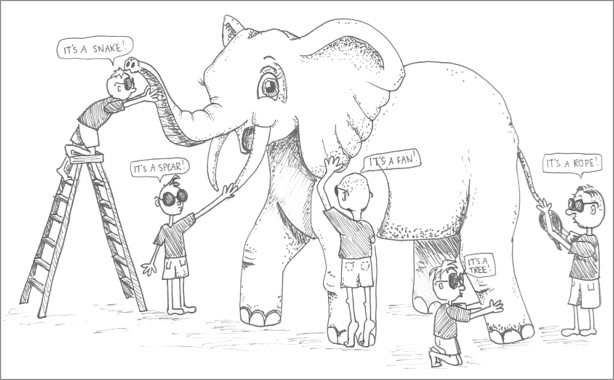

Welcome to the first post of INWYT Unraveled, a blog series dedicated to exploring our approaches to problem solving in healthcare and beyond. As we begin our deep dive, we must understand how assumptions shape our reality, distort our actions, and obscure the actual problems we need to solve.

What are Assumptions? Let’s look at some key definitions:

- Assumptions: A thing that is accepted as true or as certain to happen without proof.

- Reality: What we think is happening based on our assumptions.

- Actuality: What is factually happening without assumptions.

We are rooted in assumptions:

- We have personal assumptions.

- We are surrounded by people who share the same assumptions.

- We continually seek out others who share our personal assumptions.

Assumptions are based on our mental models and conditioning. Assumptions that inform our daily lives include:

- Cultural Traditions

- Religious Beliefs

- Scientific Theories

- Behavioral Patterns

- Personal and Collective Experiences

- Process and Systems Function and Outputs

Why do we rely on assumptions?

- We have incomplete knowledge and seek to fill in the gaps.

- We fear the unknown and seek guardrails to manage uncertainty and avoid pain.

- We’re insecure and seek safety and stability.

- We’re confused and seek clarity in our identities as individuals, teams, and organizations.

Where do assumptions lead us?

- All is well when our assumptions are aligned with our circumstances and activities.

- If things work out for us despite a deviation from our assumptions, incidental or intentional, we often attribute it to luck or good fortune.

- When what we think is happening is misaligned with what we think should be, this division creates conflict.

- When we’re in conflict, our typical reactions include frustration, fear, anger, confrontation, and suffering.

- We generally try to manage or avoid conflict because it threatens our sense of stability and security, and it hurts.

What do we do to mitigate conflict?

- We stay in our lanes: We play by the rules of our assumptions and do what’s best within their guardrails. We align with those who share our worldview while distancing ourselves from those who don’t.

- We restrict our playing field and peripheral vision: We believe our assumptions are correct, and resist looking for anything out of bounds.

- We blame others when expected results fall short: Since we think our assumptions are correct, we further assume that failure must be the fault of someone not adhering to the rules.

Let’s explore a couple of scenarios where assumptions go askew.

Education Systems

Formal education is assumed to be an essential element of success:

- The better educated we are, the more likely we are to have a stable job, the ability to support a family, and to be upstanding citizens.

- We assume that different career paths and professions have different societal value, and assign them varying degrees of social status and financial potential.

- School becomes a competitive environment where students are swept into a wave of grade-driven learning and test taking, doing their best to surf to shore with a better performance than their classmates.

- College or university is the assumed next educational step for future success, and students apply to select schools based on assumed acceptance criteria.

But college acceptance criteria can be misaligned with high school assumptions:

- Some “top-notch” high school students are not accepted into highly competitive universities, while other less conventional students with “average” high school credentials are accepted instead.

- The “top-notch” student is upset and blames a flawed admission process; it didn’t follow the assumptions, and they should have been admitted.

- The “average” student attributes their success to luck; they didn’t adhere to the assumptions and shouldn’t have gotten in.

Adverse Medical Events and Errors in Healthcare

Identifying adverse medical events and errors is one of the biggest barriers to creating sustained functional solutions in quality and patient safety:

- Despite pockets of excellence, a pervasive culture of clinician vigilance serves as the core foundation to preventing patient harm.

- We assume that established care processes and systems will not prevent patient harm unless each care team member maintains hands-on oversight of patient care.

The expectation of care team vigilance creates a problem cascade:

- When a patient is harmed, we assume that an inattentive care team member was to blame; this wouldn’t have happened had they been vigilant.

- Care team members are disincentivized from disclosing the event; they assume that disclosure will result in a disciplinary action and malpractice lawsuits.

- As a result, many preventable adverse events are not reported, and patients are kept in the dark about what happened.

- Corrective improvement is delayed or never initiated.

See the twists that these assumptions impose on the participants:

- Despite their vigilance, the involved physician minimizes attention to the event by labeling it as a complication.

- The event is not reported, and the harmed patient is given limited information.

- Upon discharge, the patient is upset and dissatisfied with how they were treated and files a malpractice suit against the physician, demanding full disclosure.

- The assumptions guiding the physician and the organization have failed and are misaligned with the patient’s expectations.

- Conflict ensues with everyone blaming the other; no one thinks that the contradictory assumptions are incorrect, but rather that they should have been adhered to.

Contrast this outcome with the same adverse event where the physician discloses what happened to the patient and apologizes:

- Rather than sue the physician, the patient thanks the physician for their transparency and asks that corrective action be taken so that the event doesn’t happen again to any other patient.

- The response and outcome deviate from the original assumptions and are viewed as luck on part of the physician and organization.

- While full disclosure was aligned with the patient’s expectations, it conflicts with the collective patient assumption that patients should sue for malpractice when they are harmed; the forgiving patient is a deviant for not having pursued financial compensation.

- The core assumptions remain unchanged.

Beware of Assumptions: Key Considerations

- Assumptions are based on ideas, not facts

- They originate from our mental models, conditioning, and experiences

- They shape our reality, adding interpretation and imagery to what we think is happening, and what we think should be.

- Assumptions are tightly linked to expectations, opinions, hypotheses, and conclusions

- They limit our ability to openly inquire and observe anything new

- What is actually happening remains largely overshadowed and invisible.

- Assumptions create division and conflict

- When what we think is happening contradicts what we think should be, we are in conflict.

- The uncertainty, fear, and anger associated with conflict become powerful reactive drivers and impediments to functional change.

- Assumptions prevent us from seeing, understanding, and solving functional problems

- Assumptions envelope functional problems in a conflict cocoon and misdirect our focus to resolving the conflict rather than solving the problem

- Conflict management becomes our problem-solving surrogate, and we end up with misdirected problem workarounds.

Questions to Ponder:

- What are some assumptions you’ve made recently that didn’t hold up in reality?

- How does your team or organization respond when expectations and outcomes don’t align?

- In your line of work, how often are problems framed as conflicts—and could that be obscuring the real issue?

- What might change if you were aware of your assumptions and started observing from there?

Where To Next?

In our next post, we’ll explore a critical question:

Is a problem always a conflict?

To set the stage, consider the following quote:

“We can’t solve problems using the same thinking that created them to begin with”

– Albert Einstein

See you next time!

–RVP

Leave a Reply