“I think, therefore I am” – René Descartes

When we look at the issues and concerns in our daily lives and the endless competition, confrontations, and violence in world events, have we accepted or resigned ourselves to the conclusion that conflict is inevitable? In other words, like our cultural acceptance that “to err is human,” have we also accepted that “to be in conflict is human?” If that is so, then our approach to conflict is immediately narrowed to reactively mitigating the manifestations of specific conflicts rather than investigating the mechanism and nature of conflict itself to see whether it is possible to move completely beyond.

We Manage Conflict Like A Chronic Disease

If we accept that being in conflict is human, then the best we can do is manage conflict. Like chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension, we can potentially slow progression and keep signs and symptoms at bay with a variety of interventions, some of which are benign and others that have significant side effects and lifestyle changes. Management requires consistent attention, monitoring, interventional adjustments, and compliance. If management lapses or is discontinued, the chronic condition worsens, symptoms return, and we are at increased risk of developing new complications. Our time and effort are focused on optimizing chronic management, limiting our ability to understand and act on the underlying mechanism of the chronic condition. We think the latter is too complicated, so we label it as impossible.

Managing Conflict in the ED: Boarding

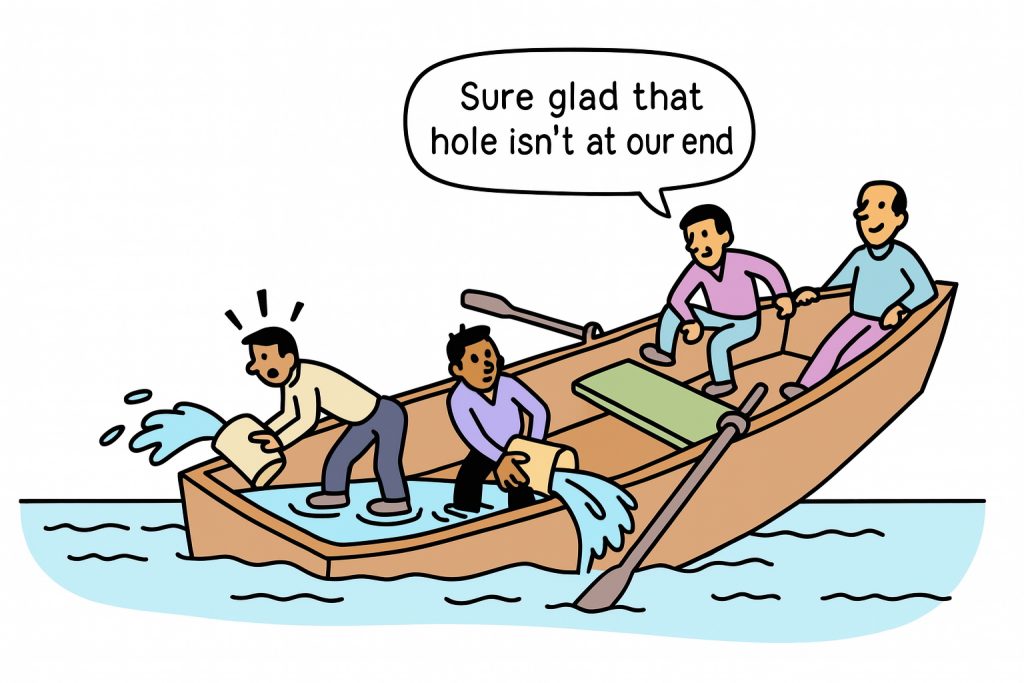

Consider a persistent hospital problem like ED boarding. Most hospital leaders believe that boarding is impossible to eliminate, and we place most of our effort on alleviating the immediate causes, signs, and symptoms, such as identifying avoidable ED readmissions after they have arrived, creating additional bed capacity in ED hallways, and optimizing inpatient care in the ED. Attempts to engage admitting services to care for their boarded patients are met with resistance because of competing staffing priorities and workflow constraints, which creates quality and safety lapses, additional workload and distraction for the ED care teams trying to manage ED patients under evaluation. We establish modest and achievable targets for improvement initiatives such as avoidable readmissions; they are often linked to financial incentives, which no one wants to lose. While our fragmented efforts are well-intended and may provide transient improvement as long as we are vigilant, we are so overwhelmed with bailing water to stay afloat that we never consider taking a deeper look to understanding the nature of the leaks.

Can Conflict Be Eliminated?

Our belief that to be in conflict is human precludes us from considering whether conflict can be eliminated. Why don’t we question this assumption and investigate whether it is possible to end conflict? Afterall, we can’t say something is impossible until we have understood what is possible. Maybe we’re taking the easy way out with the “impossible” label, or perhaps we’re reluctant because our investigation might expose other problems we don’t want to see, a Pandora’s box. Is it worth questioning the assumption that eliminating conflict is impossible? Let’s take a look at a clinical analogy that combines chronic management and elimination as critical interventions.

Treating Sepsis Requires Management and Elimination

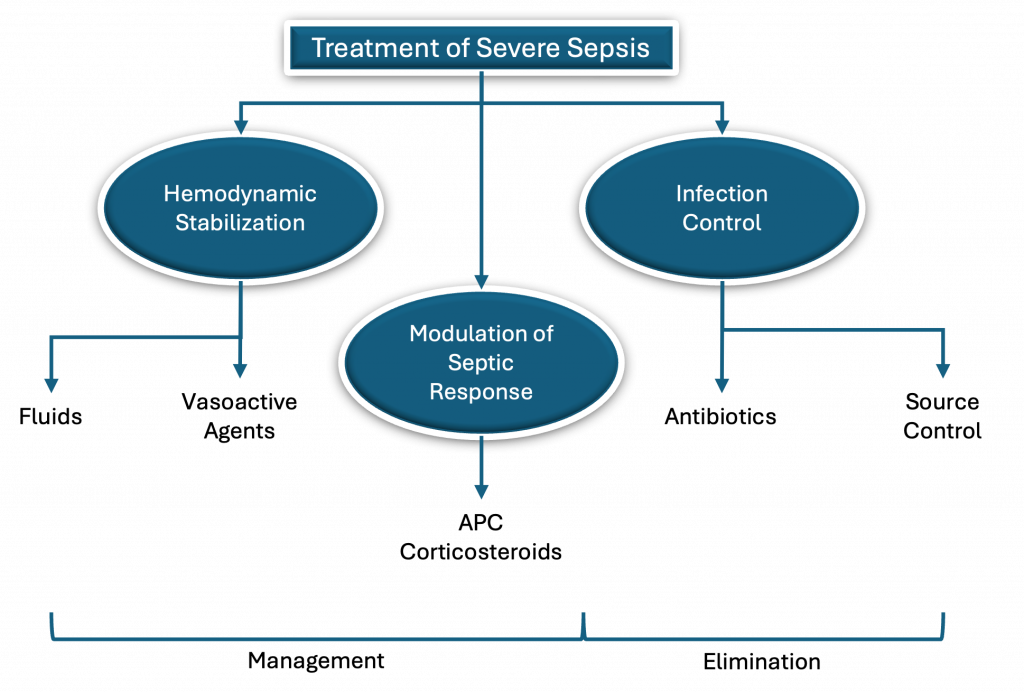

Sepsis is a life-threatening bodily response to infection with a high mortality rate when not rapidly diagnosed and treated. Medical treatment typically involves managing the signs and symptoms of sepsis with interventions such as IV fluids and vasopressors, and eliminating the source of infection with antibiotics. Patients can be transiently stabilized with supportive management, but if the management is inadequate and/or the infectious source is not quickly identified and eliminated, the patient’s condition will deteriorate with a high likelihood of death. To effectively treat sepsis, we need supportive management and elimination of the underlying pathogen.

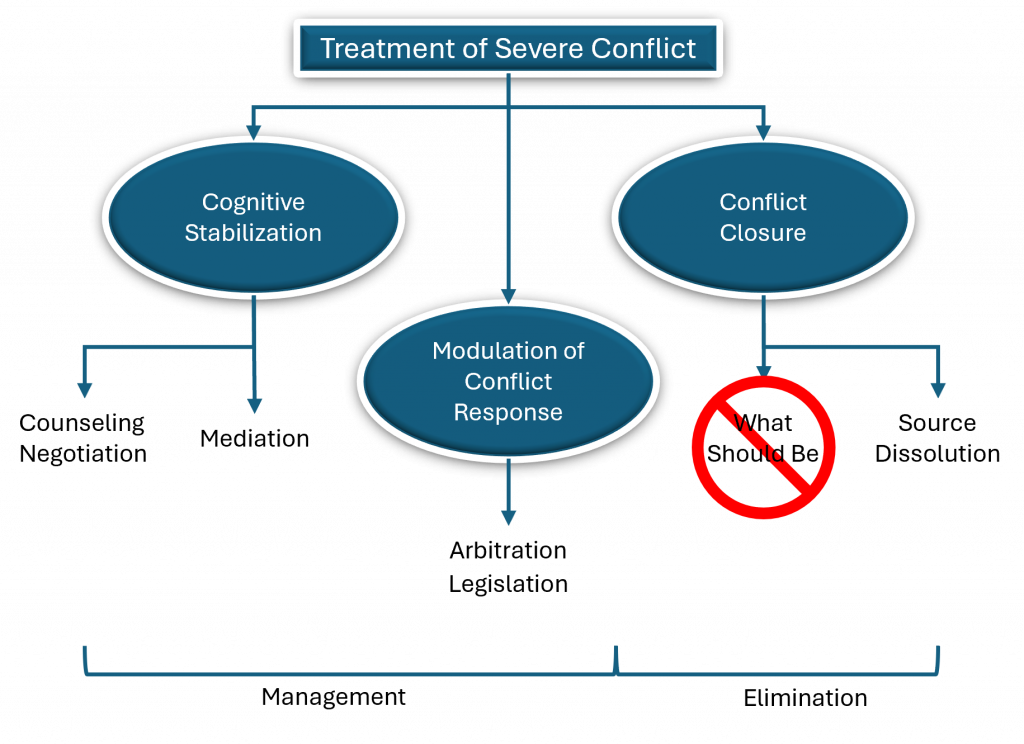

Treating Conflict like an Infection: Management is not enough

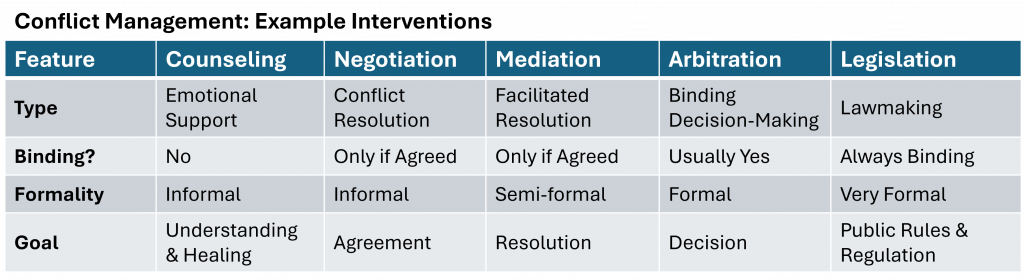

Conflict is like an infection, which can escalate from minor distress to “septic” shock with tragic outcomes from the personal to global level. We can see how conflict escalation plays out in familial or spousal quarrels, professional scope of practice disputes between physicians and advance practice providers, national sovereignty clashes, ethnic and religious intolerance. We focus our efforts on managing the signs and symptoms of conflict with interventions such as counseling, mediation, negotiation, and compromise but unlike clinical infections we rarely, if ever, understand and eliminate the operative source. As a result, our management delivers periods of simmering, and there is always the risk of rising temperature that boils over into violence, pain, and suffering.

Understanding the Thought Cycle of Conflict

We can eradicate bacterial infections because we understand the critical mechanisms and nature of the bacterial life cycle. Through that understanding, we create effective antibiotics that eliminate pathogens. If we want to eliminate conflict and its detrimental effects, we must understand and eradicate the underlying source of conflict as well.

We looked at the nature of conflict in the prior blog; let’s approach at it again from a different angle. We can begin by looking at the common clue embedded in our error and conflict statements. “To err is human” implies that we are the incorrigible source of error. Similarly, “to be in conflict is human” suggests that we are the same source of conflict. So, we must look at ourselves and understand what it means to be human.

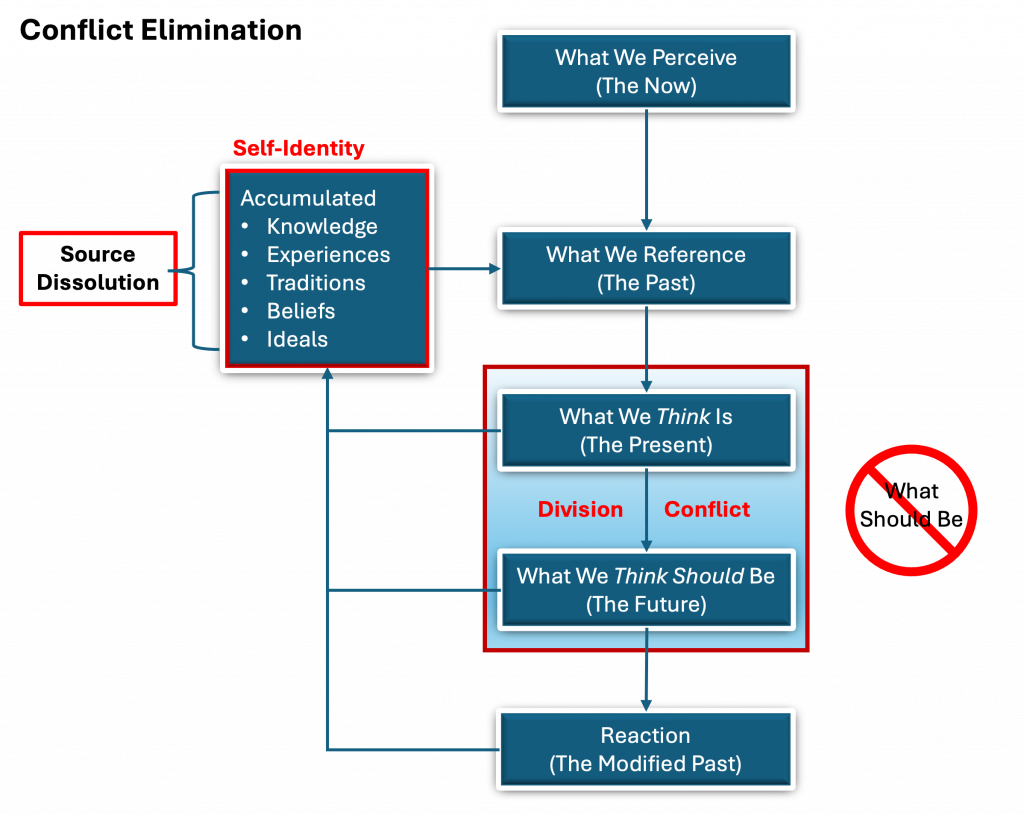

There is a well-known quote by René Decartes, “I think, therefore I am,” which links thought to our human identity. We’ve seen how thought shapes our self-identity and worldview with select memory comprised of accumulated experiences, knowledge, traditions, and beliefs. Our individual identities and worldviews divide us internally and from each other, creating conflict within and without. Thought uses our worldview to identify, interpret, and imagine what is and what should be. The contradictory division between what we think is and what we think should be is a core mechanism of thought that creates conflict. Rather than understand what is, the objective fact, we focus on what should be, the subjective ideal.

Managing Conflict Creates Conditions for Eliminating Conflict

If we believe that thought defines who we are and what it means to be human, as Descartes posits, then conflict seems inevitable. However, if we understand how thought creates and uses our identity and worldview to create conflict wherever thought is subjectively applied, we may have an insight that completely wipes out conflict.

Subjective thought divides, and that division creates contradiction and conflict. When we understand the fact of what is rather than responding to the imagined ideal of what should be, can division and conflict end? Managing the symptoms of conflict creates conditions for us to observe, understand, and eliminate the operative source of conflict. Now we are free to look, understand, and act on the functional problem that has been entangled therein.

Question to Ponder:

Like sepsis, the treatment of severe conflict requires an integrated approach of sign/symptom management and source elimination. Sepsis is avoidable when an infectious source is quickly identified and treated. Does our understanding of the mechanism of thought as the source of conflict enable us to avoid conflict altogether? Share an example where conflict was completely avoided. What happened?

Where to Next?

We’ve put a lot of attention on understanding the ubiquity of conflict in our daily lives, from its most subtle to its most extreme forms, and on understanding the nature of conflict and its relationship to thought. Hopefully, we have an awareness of our predisposition to attribute conflict to external manifestations and causes, and that we manage the signs and symptoms rather than eliminating the source. Conflict management distracts us from seeing and understanding the entangled functional problem, which prevents us from creating new and sustained solutions. Managing the conflicted problem alone results in more, better, different; eliminating conflict exposes the functional problem and creates transformation.

With our understanding of the critical mechanism driving conflict, we can now begin to explore how to transform collective conflict to collaborative problem solving. The approach to problem solving is more important than the problem itself. We’ll look at a set of core principles that, when integrated, create a synergistic power source for problem-solving tools that empower teams to create sustained solutions to complex problems. From there we’ll see how these principles are applied to a problem-solving tool that concurrently builds collaborative teams while organizing and prioritizing improvement activity.

Our Next Question to Investigate: How do systems, participatory management, and peer support principles create powerful synergies for complex problem solving?

To set the stage, consider the following quote:

“Synergy is the only word in our language that means behavior of whole systems unpredicted by the separately observed behaviors of any of the system’s separate parts.” – Bucky Fuller

See you next time!

Leave a Reply